-40%

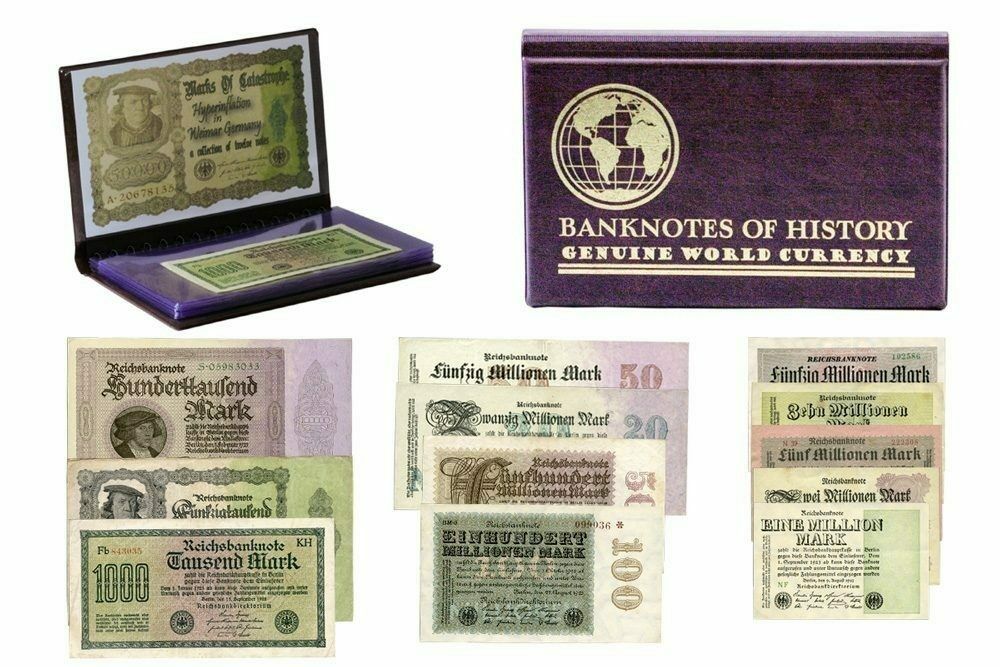

Germany Weimar Republic Hyperinflation Period - A Collection Of Twelve Banknotes

$ 66

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Germany Weimar Republic Hyperinflation Period - A Collection Of Twelve BanknotesHistorical Collection - COA & Hitory & Album Included

Marks of Catastrophe : Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany A Collection of Twelve Notes

This remarkable collection includes 12 different high denomination notes issued by the Weimar Republic during

the German hyperinflation crisis of 1921-24.

When naysayers warn of the perils of inflation, what they’re really talking about is hyperinflation, defined

as a monthly rate of inflation in excess of 50 percent. This is a chaotic period of economic upheaval, when

fixed incomes become worthless, when wheelbarrows are required to transport paper money to the

market for simple transactions, when restaurants write menu prices in pencil because they change every

hour. No modern incidence of hyperinflation is as notorious—or as historically significant—as that which

befell the Weimar Republic of Germany in 1921-24.

In 1914, Germany under the Kaiser was a prosperous country, a center of industry and culture, and

arguably the most powerful nation on the continent. The loss in the Great War, while deleterious to

national pride and disastrous to the House of Hohenzollern, was not as ruinous to the economy. Because

the theater of war was mostly in France and Belgium, Germany survived the war with its vast industrial

power intact; if anything, indicators in 1921 hinted at growth. Two years later, however, the German

economy was a shambles, its currency trading an at unfathomable one trillion marks to the U.S. dollar.

The causes of the economic collapse are complex, but they begin with the Great War. A prosperous,

heavily industrialized, and populous nation, Germany believed it would win. The government financed the

war exclusively through deficit spending, gambling that the abundant spoils of a quick victory would cover

the debt. That did not come to pass. Instead, millions of soldiers deserted the army because they were not

being paid. Thus when the war finally ended, Germany had already racked up a big deficit—and that was

before the terms of the peace were considered.

The aftermath of the war was even worse. The Treaty of Versailles compelled Germany to pay prohibitive

reparations to the Allies—in hard currency. This meant that German marks, which were no longer pegged

to gold as of 1914, were not accepted as payment. Negotiations with France, Belgium, and Great Britain

failed to convince the Allied powers to accept a drastic reduction in reparations from Germany, as they

had with Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Turkey. On 5 May 1921, the so-called “London Ultimatum”

called for Germany to pay 2 billion goldmarks, plus an additional 26 percent of the value of German

exports, in war reparations—a figure that, when added to the internal war debt, proved prohibitively

expensive. The stage was set for the financial disaster that followed.

To generate the needed revenue, the Reichsbank printed vast quantities of paper money, exchanged it for

foreign currency, and used that to pay its war debts. After the first month, the rest of the world caught on

to this financial smoke and mirrors, and the value of the mark began to fall precipitously. Meanwhile,

prices soared. Hope for any sort of return to normalcy was extinguished when the French occupied the

Ruhr valley—Germany’s industrial heartland—in J anuary of 1923, to ensure reparations were paid in

kind. Exacerbating an already chaotic market was a huge increase in commodity speculation, as

businessmen quit their jobs to engage fulltime in speculative ventures.

This remarkable collection includes 12 different high denomination notes issued by the Weimar Republic during

the German hyperinflation crisis of 1921-24.

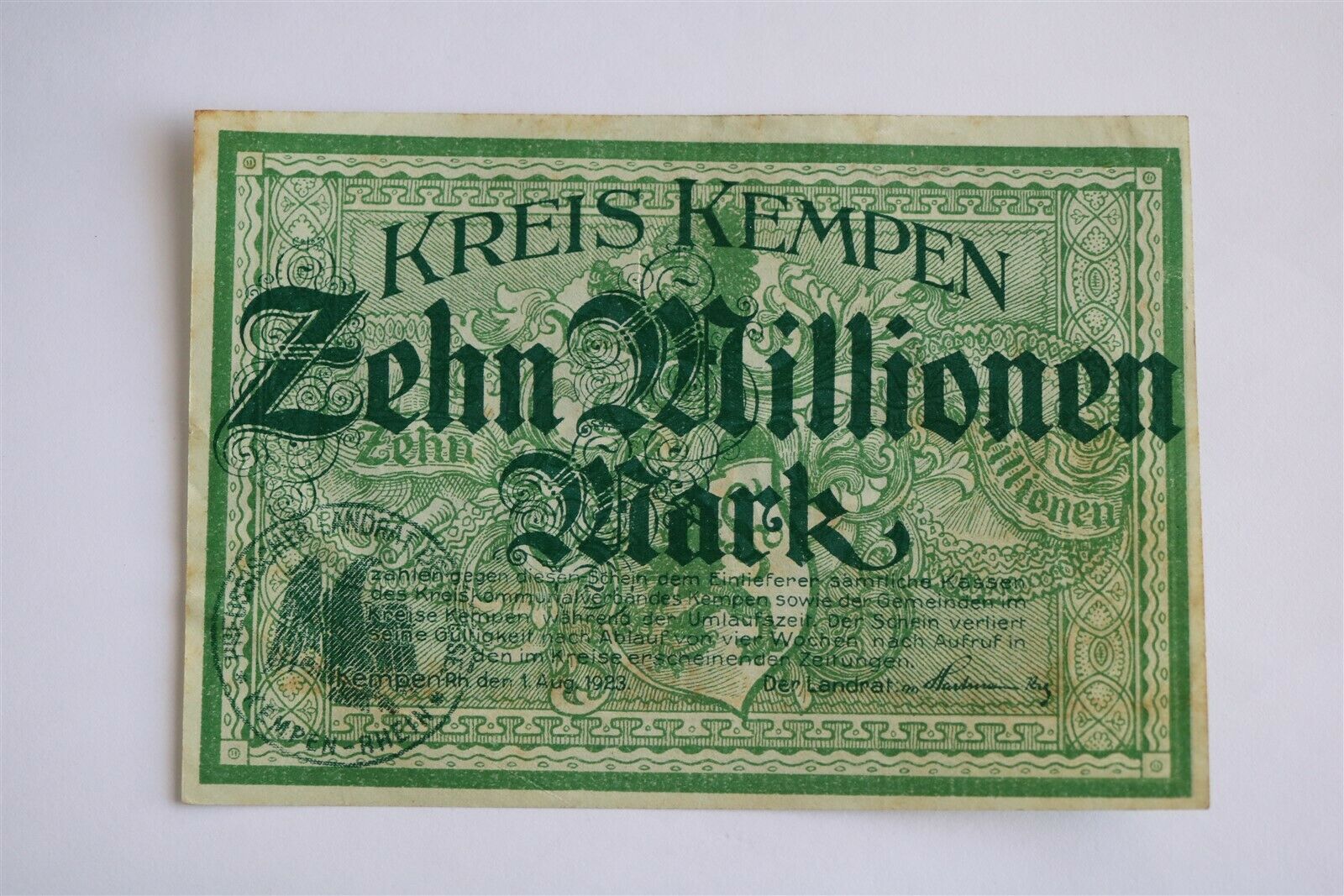

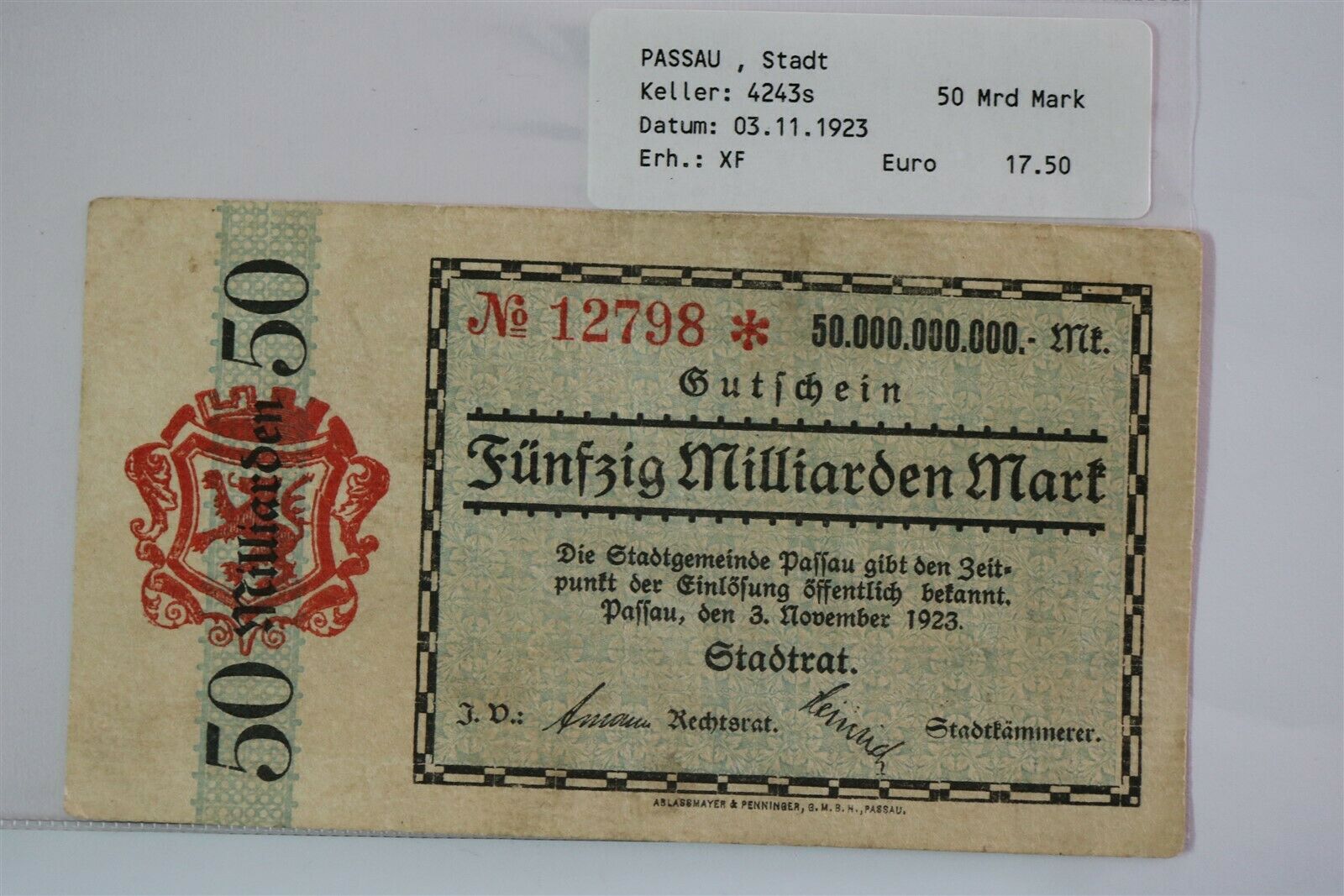

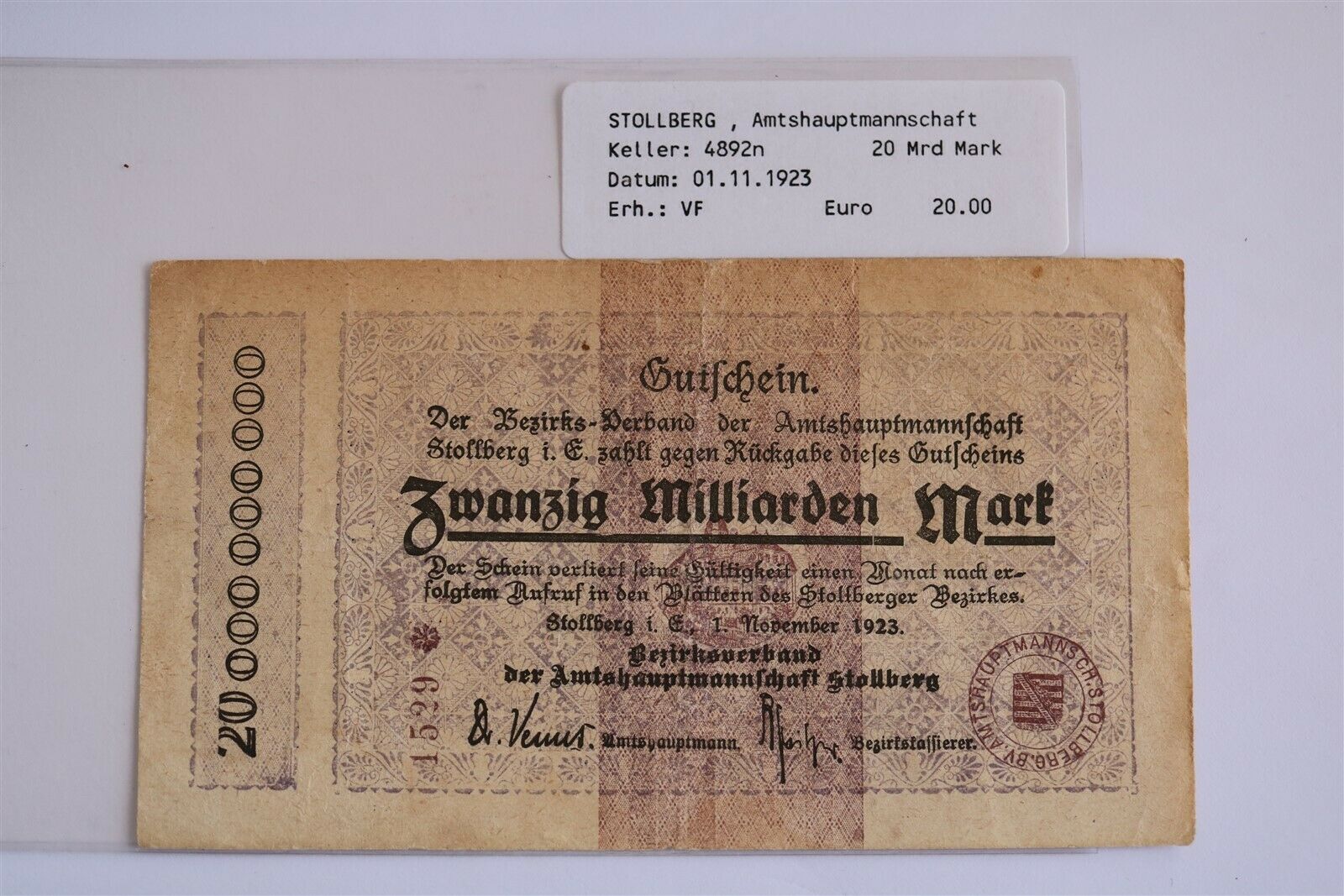

The year 1923 was a nightmare of hyperinflation. Some 300 paper mills supplied pulp to 150 printers

where two thousand presses worked nonstop, night and day, to crank out increasingly-worthless paper

money. Late in that year, a loaf of bread sold for 200 billion marks. Workers were paid two or three times

a day. They’d deliver the cash to their wives, who would rush to the stores to buy goods—only to find that

the shelves were empty. Food riots erupted. The economy fell apart, and the social order began to collapse

with it. Only when the Rentenbank established a new currency at the end of that year—with one

Rentenmark equal to one trillion old paper marks, and the money supply strictly limited—did the

economic death spiral cease.

Between 1 February and 5 November 1923, the Reichsbank had to print eleven different issues of new

notes, to account for the increasingly bigger denominations. The highest denomination in the first issue

was 100,000 marks; in the second, one million; in the third, 5 million. The highest denomination in the

final issue, printed in early 1924, was a staggering 100 billion. There were 60 different types of banknotes

issued in all. At the nadir of the crisis, the U.S. dollar was trading at 4,210,500,000,000 marks.

1. Germany 1,000 Mark |P‐76

2. Germany 50,000 Mark |P‐79

3. Germany 100,000 Mark |P‐83

4. Germany 20, 000,000 Mark | P‐ 97

5. Germany 50,000,000 Mark | P‐98

6. Germany 1 Million Mark | P‐102

7. Germany 2,000,000 Mark | P‐104

8. Germany 5,000,000 Mark | P‐105

9. Germany 10,000,000 Mark | P‐106

10. Germany 100,000,000 Mark | P‐107

11. Germany 50,000,000 Mark | P‐109

12. Germany 500,000,000 Mark | P‐110

Hold the pieces of history in your hands!

Catchy Collections.